- Home

- M. D. Elster

FOUR KINGS: A Novel Page 3

FOUR KINGS: A Novel Read online

Page 3

I stare through the glass for several minutes. But then a glint of something in the reflection catches my eye. I whirl around, anticipating someone approaching me from behind, but there is no one there. Get ahold of yourself, I think to myself. I breathe, and try to persuade my heart to slow down. But when I look back into the reflective surface of the window, I am startled to see a face, very near to mine, and I am even more startled to see it is covered in reddish fur, like a fox. I blink in disbelief. He moves as though to press his nose against my own and the specter of his face becomes eerie and bright.

All at once I hear the sound of glass shattering. White flashes of lightning blind my eyes — followed, bizarrely, by green and orange flashes. I hear a torrent of rain; see a flood of water filling the floor. Another sound rips through the air — is that thunder? Or a gun going off? Or something else… a bomb maybe?

I let out a terrified shriek and shield my face, not wanting to get glass in my eyes.

But then, as abruptly as these sights and sounds wash over me, they cease, vaporizing into thin air. The window is intact. Nothing has happened. I blink, bewildered. Perhaps I truly am losing my mind.

“Oh, no,” one of the nurses says. She rushes around to my side and guides me over to a chair. “Are you all right, dear?” Over her shoulder, to another nurse, she says in a confiding voice, “It looks as though we may have transferred her between wings too soon. The doctor is in an awful rush with this one.”

I shake myself, and try to recover my calm demeanor. “No, no,” I say. “I’m fine. Really, I’m fine.”

She looks dubious.

“I’m so sorry,” I add, hoping to show her that I am sane enough to feel humiliated by the outburst, and I can see her soften somewhat. “I think… I think some of my memories may be coming back to me,” I say. I wonder if this is true. Flashes of white light — was I remembering the hurricane? The night of my stepfather’s shooting? Perhaps. Whatever it was, it wasn’t pleasant.

The nurse appears to read my thoughts. She pats me on the hand as though to comfort me. “You’ve had a terrible experience, my dear,” she says. “Please, though, for everyone’s sake, try not to let your emotions get the better of you. You cannot imagine how easy it is to get the other girls worked up, and once one or two get started, well, the whole room goes!”

I nod. With a final pat of my hand, she leaves me to relax in the chair alone. I am suddenly exhausted. I want the nap I refused to take earlier.

I barely remember the rest of the day. I have other interactions, more girls talk to me, but I am no longer fully present. I notice they are never very fussed when I am slow to answer — I suppose there are a lot of Ellens here: girls who never answer. Life in an asylum requires a great deal of patience. At six o’clock, the nurses and orderlies herd us all to the cafeteria where I pick at a very bland, gravy-less mound of mashed potatoes along with something I think is meant to be catfish etoufée.

The hours wear on, while the surreal atmosphere of the asylum does not wear off. Eventually bedtime is announced. The nurses round us up, clapping their hands. I follow the other girls as we are herded into the dormitory, and find my way to my assigned cot. I am to pass my first night here. Or — rather — the first night I can remember. I cannot imagine sleeping in such a place, with its eerie stirrings and cold walls. And yet, if I believe what they tell me, I already have.

CHAPTER 4.

“I’m Lucy,” a voice says. I’m struggling into my nightgown, and only have it halfway over my head. When I manage to get my head free, I find myself looking at a girl near my own age. She is dark-haired and quivering with nervous energy. Her eyes shine bright like a forest animal’s.

“You’re between me and Ellen,” she says, pointing to where Ellen sits on her own cot, staring vacantly into the distance. “I think they lump us together depending on age. Which is silly. I feel much older in my soul. I’ve been to more exotic lands than most people three times my age. It matures you, you know.”

“Yes,” I agree, briefly hopeful she might know my native land. “Where have you been? Europe? Asia? Africa?”

Lucy shakes her head. “None of those,” she answers disdainfully. “I’ve traveled much further abroad than that.”

I frown, not sure I understand.

She fidgets, and points again to Ellen. “Don’t let her fool you,” Lucy says. “She makes out that she’s the quietest one out of all of us, but she snores like a bear. I’ve complained, but the nurses don’t care.”

“Hmm.” I nod.

“I’m sorry about your stepfather,” Lucy adds in a softer voice.

This gets my attention. I want to ask her what she knows, and how. Before I get the chance, we are ordered into bed.

“LIGHTS OUT!” calls one of the nurses.

All twenty-four of us climb into our cots and wriggle under our scratchy blankets.

“Now, behave, girls… sleep well. We’ll be making our regular rounds.” She flips a heavy switch and the electric lights overhead go dark.

Sleep does not come to me right away. It is a curious thing indeed to sleep in a room with twenty-three other women, some of them tied down to their beds in restraints, all of them sighing or snoring or whimpering or simply rustling about under the bed-sheets. While you sleep, your brain listens to all of this somehow; you might doze, you might even dream, but you never quite dip all the way under the black waters of true unconsciousness.

The nurses have left a dim electric lamp switched on upon a little table in the middle of the room, partly for those girls who are troubled by the dark, and partly so that we are easy to count when the staff performs a twice-nightly bed check. The lamp is covered with a red shade — presumably a tactic intended to make it easier to sleep for those of us who prefer the pitch-black dark, but the main result of this effort is a very sinister, devilish glow.

I lose all sense of time. Finally, after a dedicated period of counting sheep, I manage a light doze. However, my slumber is interrupted, and when I wake up and see something I cannot explain.

First there’s a chill, and I feel the hairs on my neck rise. I open my eyes and see a figure standing over me. For several seconds, I remain convinced I am still asleep and dreaming, for what I see before me is not humanly possible. It is a man, dressed in a blue velvet waistcoat and impeccably tailored suit, a silk ascot around his neck and leather elbow-patches on his jacket. He is tall, slender, and dapper in every way.

He also has the head of a fox.

Unlike the reflection I thought I saw in the window, this creature is standing before me — correction: standing over me — in the flesh. I gasp, too shocked to move. The fox-man does not appear perturbed by my obvious distress. He leans even further over my pillow, his yellow-fox eyes scrutinizing me as though taking stock of every detail of my face, his fox-nose sniffing and his whiskers twitching at regular beats throughout this inspection. His glossy fur shines intensely orange in the red lamplight. Frightened, I look to his hands: I see he has human hands and is wearing gray leather gloves. He smells of saddle leather and of cologne; as he leans closer, my nostrils fill with the scent. Frantically, I cast a glance around at the other beds. Is anyone else awake? Can anyone else see what I am seeing?

“What do you want?” I demand of the creature. He shakes his head — I see the fur shifting gently with the movement — and holds a single, gloved finger to his lips to signal his desire for silence. Then he makes a graceful sweep of his arm, referencing — I think — the sleeping girls all around us. His yellow eyes never leave mine, and as I look down the length of his muzzle, I swear I see the corners of his fox lips curl: a small, conspiratorial smile.

Suddenly, he turns and dashes out of the room, his footsteps making no sound as he moves across the floor. His coattails vanish through the door while I lie there, frozen. My heart is pounding. But no more than five seconds pass before I am out of the bed. I leap to my feet and run after him, hardly cognizant of what I am doing. I chas

e after him; it is dark but I can see his half-human, half-animal silhouette moving through the labyrinth of corridors.

“Wait!” I cry, but he does not heed me. He periodically casts what strikes me as a friendly, amused glance over his shoulder, yet nonetheless he keeps running at a brisk clip. We go down hallway after hallway, making turn after turn — winding, I assume, into yet another wing of the hospital.

“Wait! What is this? Who are you?”

I shout all of these things, but he continues to run, and I continue to follow. I am surprised no one hears us and that we do not run into any hospital employees; every corridor he turns down is curiously vacant. I wonder again if perhaps I am still sleeping, but the details seem too vivid, too real. I think: This is actually happening.

“Wait!” I cry again and again. But he moves on.

Finally, he puts some distance between us, and I fear I am about to lose him for good. We go down several flights of stairs, winding deeper and further into the bowels of the asylum. The white-painted hospital walls give way to crumbling old brick; I understand on instinct we have reached some kind of basement level, that we are lost in the maze of the hospital’s underground foundations.

I hear a heavy door slam, and when I turn the corner, it is clear he has disappeared through it. It is also locked.

I am dizzy with running, my chest is heaving, my cheeks are burning. I am certain my face must be bright red with exertion. I step back to get a better look at the door. It is wooden: made of oak, I think, very old, and mostly plain, save for an ornate handle with an oddly shaped keyhole. The metal plate around the keyhole is stamped with an intricate design that resembles the four suits of the playing cards: clubs, hearts, spades, and diamonds. Or perhaps I only think so because I have spent the better part of an afternoon watching a group of mental patients playing nonsensical card games? It is hard to say. I am so tired, so out of sorts.

I linger there for several minutes, hesitating, not knowing what to do, but after a while it becomes quite plain: There is nothing to do. I am a lone girl, standing before a locked door in the basement of a mental hospital. I believe I have just chased after a half-human, half-animal fox-man, and I’m more than a little worried that means I am better suited for my present environment than I care to admit.

Slowly, and as quietly as possible, I retrace my steps to the dormitory. This is not easy. The fox led me through such a maze-like path; I must pay intense attention to find my way back. Of course, now I wonder if there was ever even a fox at all. I hear my own imaginary voice telling the story to a nurse, and realize I wouldn’t believe myself. It is entirely too fantastic, too impossible. Perhaps I dreamed it. Perhaps I am sleepwalking right this very minute.

Eventually, I find my way back to my assigned dormitory. Not a single girl stirs as I re-enter the room. I sit down on the bed, still thinking about what I am now convinced was an elaborate hallucination, my uncanny adventure chasing after a fox-man. But when I swing my legs up and twist at the torso to lie down under the cool sheets, I freeze just before my face hits the pillow — for there, resting in the dead center, is some sort of foreign object.

It is a key.

I pick it up and look at it. It is made of brass, and is slightly tarnished with age. The teeth of the bit are shaped very strangely, and the bow of the key is a flat medallion, imprinted with the four playing-card suits: clubs, hearts, spades and diamonds. I stare at it in disbelief.

But before I can make a more thorough inspection, I hear the sound of footsteps in the hall just outside our dormitory. It is one of the nurses, coming round to perform a routine bed check, ensuring we are all in our beds, asleep. I hastily shove the key under my mattress and dive under my sheets, closing my eyes and pretending to be asleep. The door is open a crack. I hear its hinges groan ever so slightly as the nurse pushes it a little more open, craning her neck to count all our bodies in the dim red haze of the lamp.

CHAPTER 5.

The fox-man has stirred up a distant memory of something, but I cannot say exactly what; I can only feel it buzzing dimly in the back of my brain. Perhaps it makes sense that, if I were to hallucinate an intriguing nightmare of a creature, it would have the head of a fox. As a child, my most treasured possession was a book of fairytales, and my favorite story was about a rather lordly fox, famed for his dapper manners and ingenious cunning. It also wasn’t uncommon to glimpse a real fox from time to time in the place where I grew up. I would see them capering about in the wild, peeking slyly at me from between the trees, doing what it is foxes do.

I suppose this is the moment to explain that I didn’t grow up in New Orleans, or even America, for that matter. I was born in a far older place — in a place that hardly seems real to me now sometimes — across the sea in Belgium, in a little cottage nestled deep in a place we called the Blue Forest. The “Hallerbos” — that was our word for it, so named for the thick carpet of bluebells that would blanket the forest floor every spring.

I recall being a happy, shoeless child. I spent all my time in the damp, mossy woods. Birches and oaks, pale as ghosts, kept my whispered council and whispered back to me; there were volumes of tales to be read in each glittering snail’s trail. I can still recall how I collected the piles of fur and tiny bones left behind by the owls, and how I pretended they were fairies’ bones, that a witch was leaving me signs.

“Dear dochter,” my father often said to me upon hearing me explain my latest findings in the woods, “what a vivid imagination you have!” He had a thick blond beard and eyes that crinkled at the corners like in illustrations I’d always seen of Father Christmas.

“Too vivid,” my mother warned, smiling with her pretty china-doll mouth and shaking a finger at me. “Dream all you like, but take care to keep your wits about you in the woods, ma petite. There are no witches, but there are certainly bears, and it would only take one of their kind to make short work of a small child like you!”

To my father, my mother spoke his regional dialect of Vlaams — Flemish. To me, she spoke her native tongue, French, with a sophisticated accent that insinuated a more urban setting than our mill. The fact that my father spoke Flemish, worked with his hands, and hailed from the backwoods meant they might have been star-crossed lovers if they had not been bound together by that which made them even more a minority within the world we knew: Their faith. Despite all the other differences that set their two families apart, they were alike in that they shared the Jewish faith. And while their kin did not enthusiastically endorse their match, they accepted it; at least my parents were united under the shelter of the temple.

I had a dim sense of my mother having come down monetarily in the world in order to marry my father, but I never detected a single ounce of regret in her eyes or in the lines of her mouth. They were happy and made an appealing match: My father with his twinkling eyes and easy manner, my mother with her haughty, round-apple cheekbones and wide-set eyes. She was — and still is, for that matter — the most beautiful woman I have ever laid eyes upon.

We were not rich, but in the memories I have of my childhood, we possessed everything we needed. We lived the sort of simple life that does not quite exist in the world I have come to know since; there is certainly no version of it I recognize here in America. My father was a woodcutter, our stone house sat over a little brook and was equipped with a small waterwheel and mill; people paid us to grind their grain. My mother took charge of my schooling. Once a week, on Saturdays, we hitched our wooden trap-cart to the strongest of our draft horses, and rode into town to attend Shabbat. The congregation — most of them belonging to the wealthy merchant class of Brussels — perceived us as backwater yokels and treated us accordingly, a fact I have only come to see clearly in retrospect. It certainly has a rustic charm, I remember one old woman saying in a charitable tone about a dress my mother had sewn for me. At the time, I took it as a compliment, smiled and blushed with pride.

You might assume being raised in such a rural se

tting might have limited my ambitions, but I assure you, the woods had quite the opposite effect on me. I dreamed of growing up to become — though it may sound queer now, given where I find myself at present — a doctor someday. No one told me little girls didn’t often grow up to be doctors, and because my father doted on me and indulged my every eccentric whim, he encouraged me by saving scrupulously and spending what little money we had on beautiful anatomy books, the color tracings on their onionskin paper revealing layer upon layer of organ, bone, and skin. I turned the crinkly pages with my small, chubby hands, dazzled by the human body as it came alive in rich purples, saffron yellows, bile greens, royal blues. I memorized folk cures, the Latin names of plants, a long list of recipes and poultices.

And yet, when it truly counted, my beloved science failed me; there was no poultice that could heal my father when he got sick. It began with a cough, but in time, acquired the telltale death rattle of consumption. He lay dying for months; I recall running deep into the woods in a selfish attempt to spare myself the sound of his terrible coughing, a noise similar to a seal barking, a sound that made me cringe. All too quickly, the tiny red pinpricks on his handkerchiefs metamorphosed into heavy spatters of blood. Whenever she could afford to do so, my mother brought the doctor to him, and then, after a while, she brought the doctor less and less, until finally she began to return from town in the trap-cart with Rabbi Jacobs instead.

“I ask God, why now? My timing is terrible,” my father complained to my mother, again and again. “The news from Germany grows more worrisome every day. Fewer and fewer families want to be seen at temple; they can hardly be blamed. I fear war is coming. You and Anaïs will not be safe here for much longer. Promise me you will take your old name back again, promise me you will leave for someplace safer, promise me you will hide.”

He said this every day for three months. That is, he said this every day for three months, and then one day his lips ceased to move, the crinkles dropped forever away from the corners of his eyes, his pupils faded to gray and his blue irises turned the color of milk gone bad. I watched as my mother, delicate and porcelain-skinned, her flaxen hair with its perpetual halo, spent the better part of two days digging his grave, wiping her sweaty brow as she persevered.

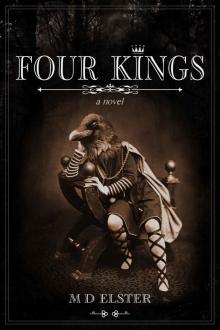

FOUR KINGS: A Novel

FOUR KINGS: A Novel